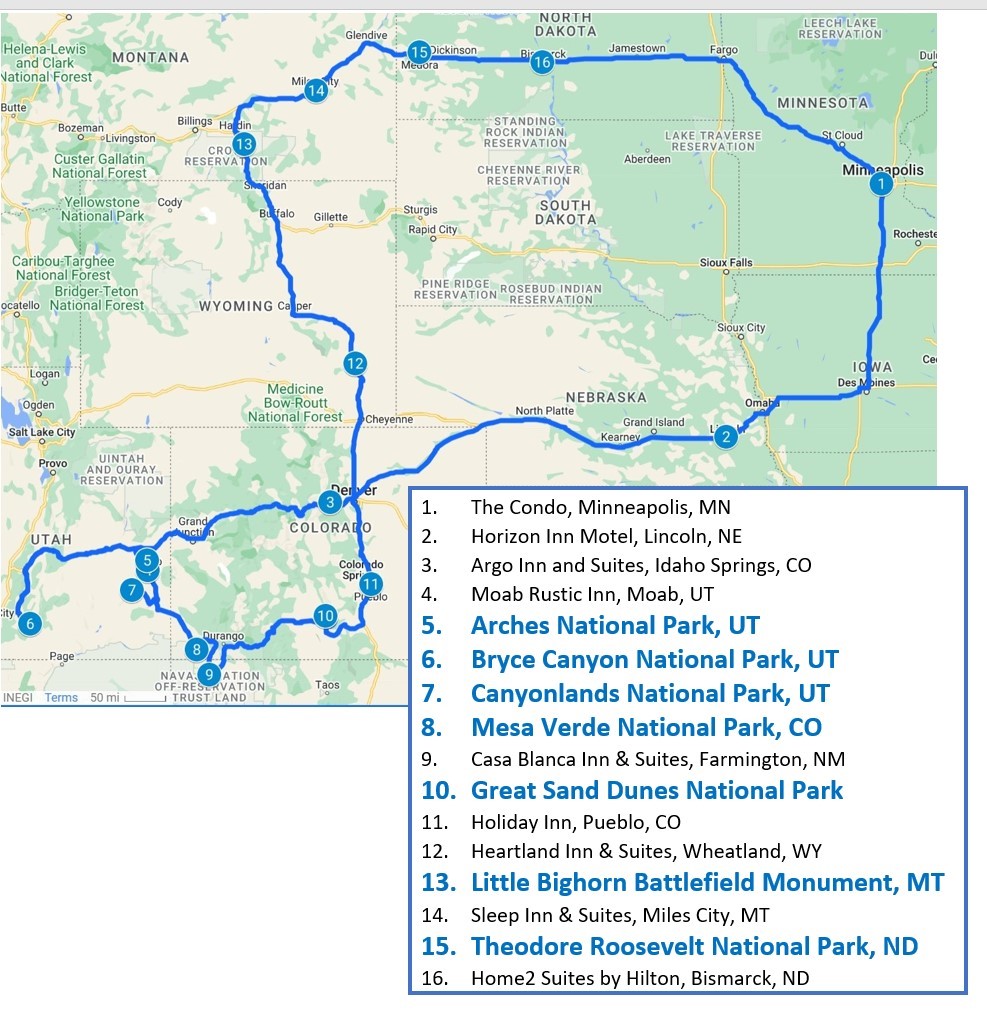

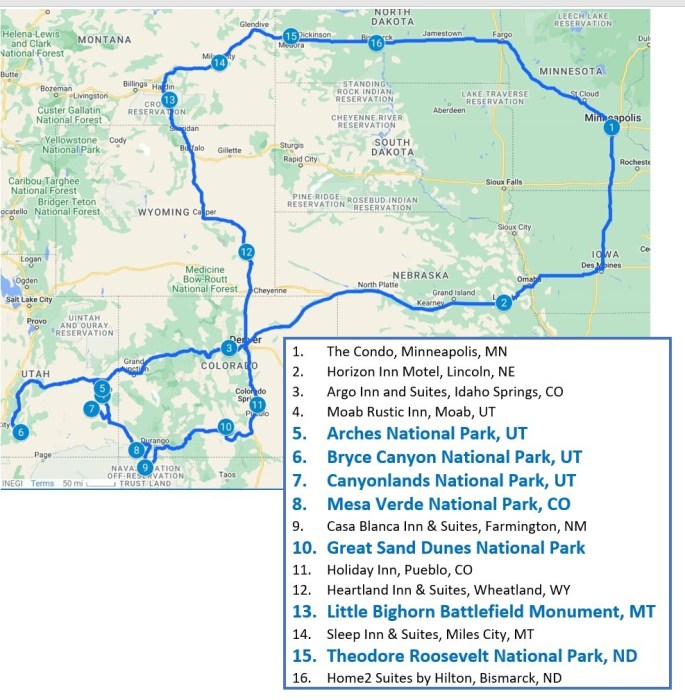

In Part 1 of this travel blog, I began the description of our recent 4,128-mile road trip, during which we visited six National Parks and one National Battlefield. As a reminder, here’s a map of the journey:

I’ll pick up the narrative again after our visits to the three National Parks located in Utah.

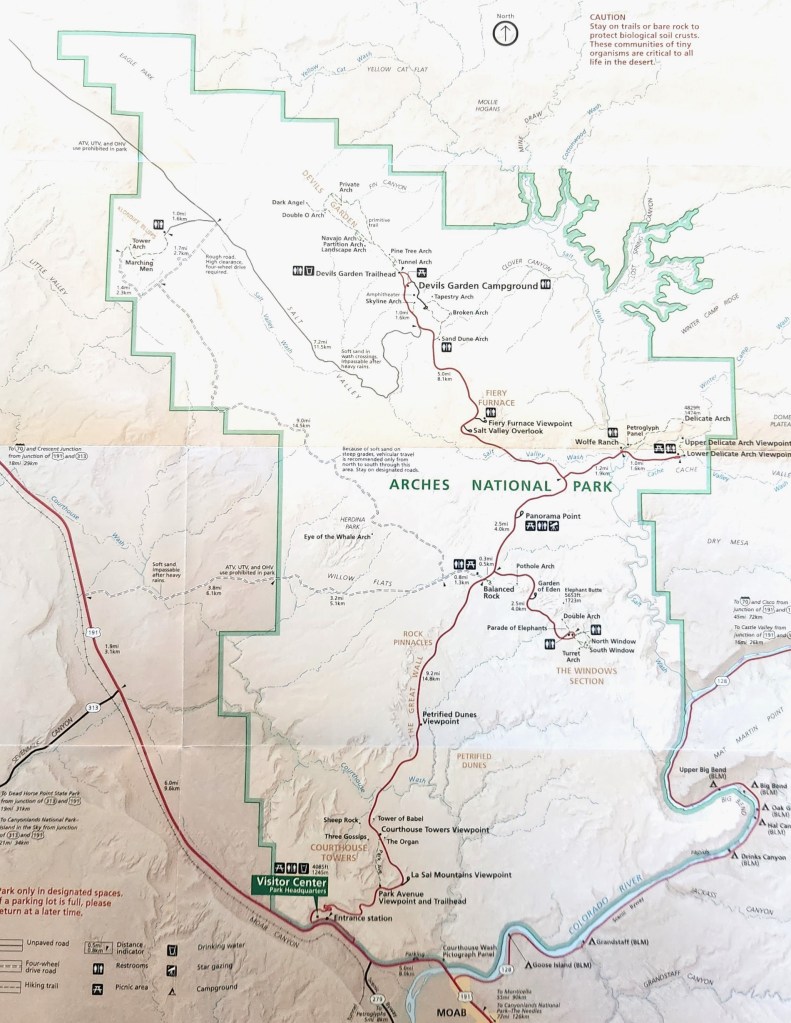

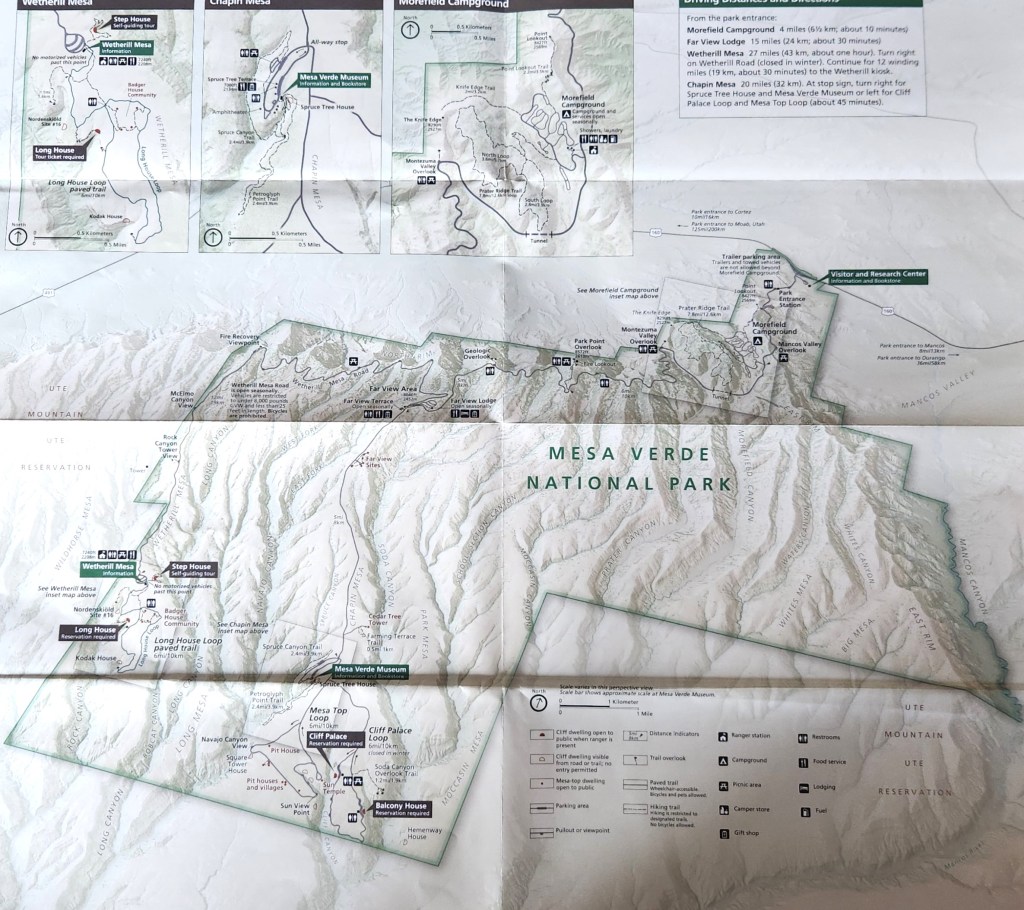

Mesa Verde National Park (October 9): I’d never heard of this park before the trip, but Pat suggested we check it out. The name for the area, which translates as “Green Table Mountain,” was coined by early Spanish explorers who noted the unusually lush greenery on flattened mountain tops separated by canyons. This was a misnomer, however, since the top of a mesa is almost perfectly horizontal, whereas the flatlands in the park actually are inclined at an angle of 7 degrees toward the south. Such an inclined, flat surface is known geologically as a cuesta, so that the “proper” name for the park perhaps should have been “Cuesta Verde.” At any rate, the park is very picturesque, with a well-maintained road that winds among the canyons to provide access to the various points of interest. Here’s a map:

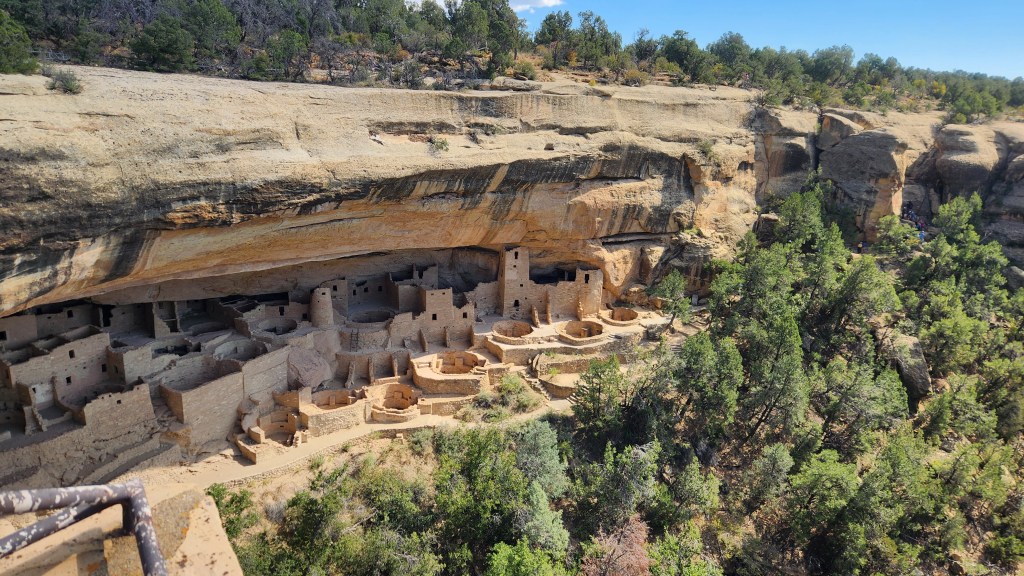

The cuesta top land is covered by soil, providing a much more fertile climate then the surrounding desert land. As such, it became an attractive home for the Pueblo people who began growing corn in the area as early as 1000 BCE and lived in villages on the surface near the crop fields. The people flourished as corn production increased and a thriving trade economy developed, with the population of Mesa Verde reaching about 40,000 at its peak in the 1200s. Around that time, the inhabitants began constructing and moving into cliff dwellings adjacent to the flatlands, which provided access to potable water via seep springs, protection from heat and rain, and places for storage of grain, clothing, and manufactured items such as baskets. One of the largest of these dwellings, known as the Cliff Palace, is a main feature of the National Park.

The highlight of our visit to Mesa Verde was a ranger-guided tour of the Cliff Palace. On the evening before our visit, we obtained tickets for a 1:30 PM tour on October 9 ($8.00 apiece) using my Recreation.gov app. We arrived at the Visitor Center around 10:30, watched a nice movie about the park (of course!), and then ogled the spectacular scenery while driving to the Chapin Mesa area.

Once at the Chapin Mesa area, I bought a souvenir T-shirt at the Mesa Verde Museum and we ate lunch at a nice cafeteria before our tour. Access to and exit from the Cliff Palace was a bit challenging, including stone steps, some narrow passages, a path that was precariously close to the cliff edge in places, and even a series of wooden ladders –the ranger was very careful to stress the hazards before we started – but the tour was well-worth it. I highly recommend it for anyone traveling to Mesa Verde, as long as they are fit enough for the climb down and out again. There were a couple of people on our tour (out of about forty total) who seemed a bit wobbly to me, but everyone managed to navigate it safely.

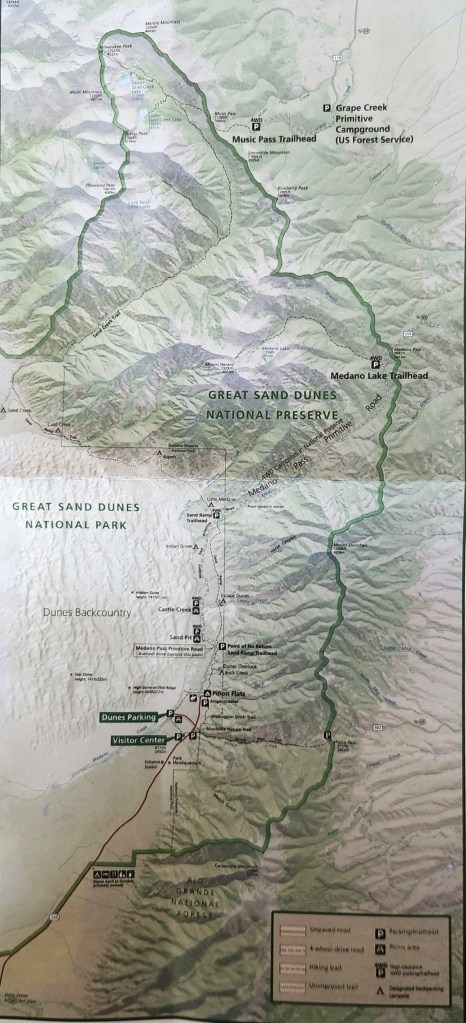

Great Sand Dunes National Park (October 10): This is another one I had not heard of before this trip, and once again I give credit to Pat for steering us there. After driving for about four hours from the Casa Blanca Inn, we were approaching the National Park from the south over a flat plain that extended for many miles with a view of some mountains in the distance, and I began to wonder if we had taken a wrong turn since there appeared to be nothing of real interest on the horizon. However, a huge pile of sand gradually began to take shape and we eventually came to the park entrance sign.

We proceeded to the Visitor Center and, naturally, watched a movie about the park and bought a souvenir T-shirt. (Perhaps you’re beginning to realize that we are creatures of habit.) The film was absolutely mesmerizing to a fluid dynamicist such as myself. What does a huge sand dune have to do with fluid dynamics, you might ask? Plenty, it turns out. I learned that the Great Sand Dunes developed over thousands of years, beginning as sediment deposited in ancient lakes. As the climate warmed, the lakes disappeared, leaving a vast layer of sand behind. Predominant winds from the southwest blew much of the sand into a low curve of the Sangre de Christo Mountains, and periodic storm winds from the mountains pushed sand back in the other direction, causing it to build up into the immense dunes. The dune structure now maintains itself through an annual cycle as follows: the desert winds blow sand into the mountains during the fall and winter seasons, and then spring and summer floods wash sand back down via Medano Creek, which borders the sand dunes to the east and south. Another fascinating aspect of the system is that the water flow in Medano Creek exhibits a pattern of waves that is unique in the world due to the ebb and flow due to the large quantity of sand carried by the water. The only disappointment in all this was that, while the film included beautiful footage showing the water flow, the actual creek was completely dry at the time of our visit, as it always is in late fall and winter. In other words, a return visit during the spring or summer will be an absolute must.

We did spend a couple of hours exploring the park, first walking around a nice loop trail near the Visitors Center, which offered great views of the dunes and the mountains and also had signs identifying the various species of local foliage, and then driving to a parking lot with access to the dunes. We walked for some distance on the coarse, khaki-colored sand, which made for very tough slogging. I found the immensity of the dunes very impressive, but in fact they were neither as accessible nor as interesting as the dunes at White Sands National Park, which we visited back in 2020, where the dunes of fine, white sand are easily accessible and more changeable in the wind. All of which again points to the need to visit Great Sand Dunes at the proper time of year, when the water is flowing.

Little Bighorn National Battlefield Monument (October 12): I first learned about the battle of the Little Bighorn some 65 years ago, when I was a young boy. At that time, it was universally referred to as Custer’s Last Stand and portrayed as a tragic loss in the righteous war to subjugate the Native people. One of the first things I saw that presented somewhat of an alternate view of the battle was the 1958 movie, “Tonka,” starring Sal Mineo in a non-PC role as a young Lakota who captures and tames a wild stallion (the titular Tonka) before eventually joining Custer’s 7th Cavalry and surviving the battle. I suspect the film was actually quite biased, but somehow it sparked an interest in me and planted a seed of doubt about just how “righteous” the white man’s war actually was. I have since read many things about the conquest of the Native peoples, George Armstrong Custer, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and the battle at Little Bighorn which have confirmed those early doubts. I also remember seeing an episode of “The Twilight Zone,” in which three US Army soldiers on a tank training exercise find themselves retracing Custer’s movements – after some rather mysterious goings on, the final scene shows the three men’s names on grave markers at the Little Bighorn Battlefield site. All of this background left me with a curiosity to see the actual battle site. Since we were traveling not too far from it, I suggested that we add it to our itinerary.

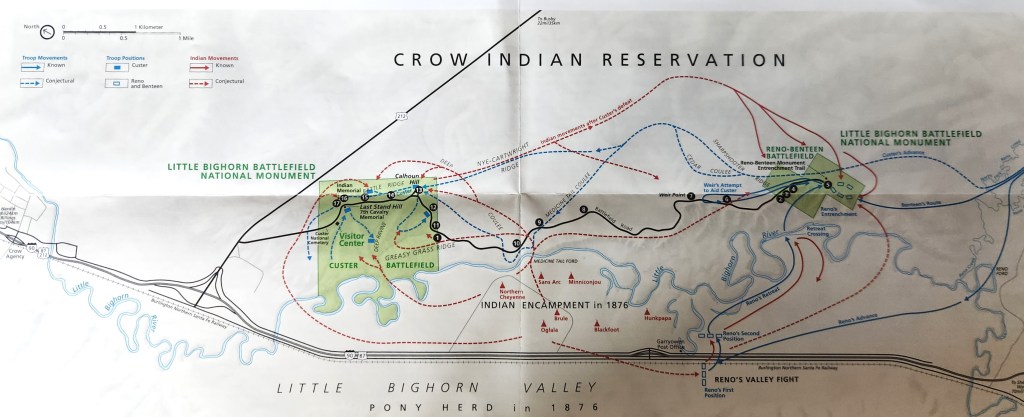

The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument was originally established by the Secretary of War in 1879 as a National Cemetery to commemorate the battle and preserve the graves of the soldiers and their allies who died there. In addition to those who died in the 1876 battle, the site includes graves of many hundreds of soldiers who subsequently served in the military in an area called Custer National Cemetery. The site was transferred to the National Park Service in 1940 and eventually given its present name in 1991 by an Act of Congress, which also decreed that an “Indian Memorial” be added to the site near Last Stand Hill. Here’s a map of the site:

We spent about an hour walking around the area near Last Stand Hill and the newer Native People’s memorial and then driving along Battlefield Road to see the various points of interest. In addition to white gravestones marking places where 7th Cavalry soldiers fell, newer, granite markers have been added to mark places where some of the opposing Native warriors died. The site was interesting, and I was pleased to see that the NPS is trying to present a more balanced view of history than I remember from the 1950s. I would hope that all Americans can agree that this is a good thing (though I have my doubts given ongoing efforts by many to recreate the 1950s version of history).

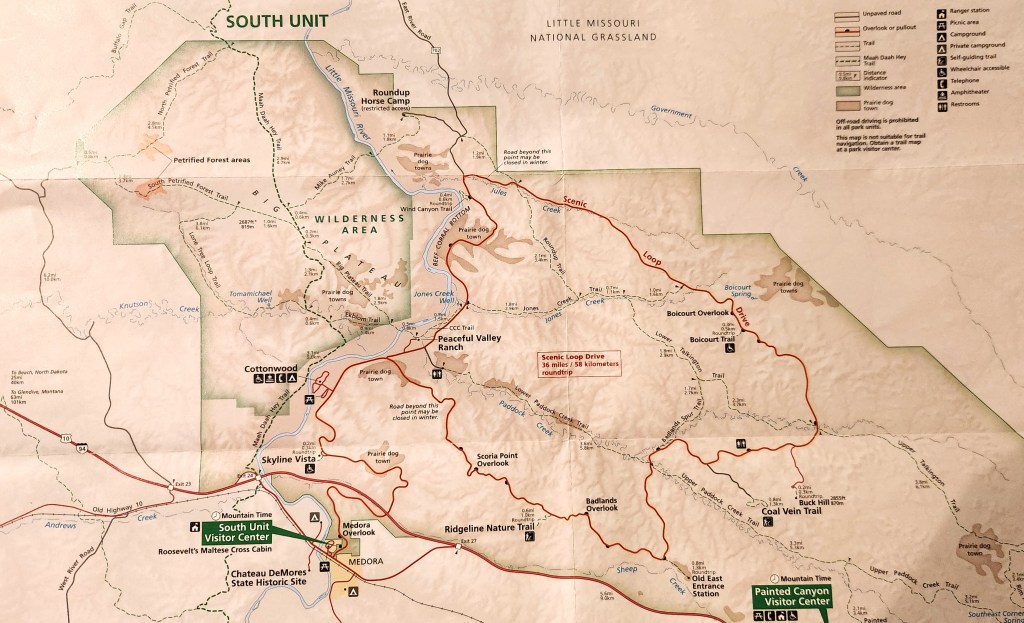

Theodore Roosevelt National Park (October 13): This was the final stop on our road trip, easily accomplished since we were driving right past it on I94 as we headed back toward Minnesota. The park was designated to honor the man known as the Father of the National Parks, which have become Theodore Roosevelt’s most lasting legacy. What is now called the North Unit of the park was originally designated as the Roosevelt Recreation Demonstration Area in 1935, before being transferred to the US Fish and Wildlife Service and renamed the Theodore Roosevelt National Wildlife Refuge in 1946. What is now called the South Unit was established as Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial Park in 1947. The North and South Units, along with the Elkhorn Ranch Unit, were finally designated as Theodore Roosevelt National Park in 1978.

We arrived at the South Unit Visitor Center at about 10:30 AM. This time, after viewing the park movie, I bought a souvenir sweatshirt, rather than a T-shirt (a near-radical departure from past practice). We spent about three and a half hours driving along the Scenic Loop and stopping frequently at various points of interest and to take a couple of short hikes. Since I’m running out of steam, I’ll just share some photos and call that good enough.

Scenery Along the Way: In addition to the main attractions described above, we also enjoyed beautiful scenery we encountered during many of the major stretches of driving. These sights only added to our enjoyment, so I thought I’d leave you with a few miscellaneous photos we took, some through the car windows and some from roadside stops.

That wraps up my documentation of this fabulous trip. I won’t include a lengthy discussion of our Tesla Model 3 EV this time, as I did in relating our April trip to the Great Smokey Mountains. Let it suffice to say that this trip again showed that taking a road trip in an EV is easily done, requiring only a little more planning and patience than driving an ICE car. The Tesla performed very well throughout, and we had no problems finding available chargers. One difference on this trip was that we encountered other EV brands using some of the Tesla Superchargers, specifically including several Rivians and one Mustang Mach E.

Just to let readers know, you won’t have to wait too long for my next travel blog installment. Next up will be another Viking River Cruise, this time to Spain and Portugal in November. Bye for now!